|

|

|

The Teachings of Buddhism

PART I

Chapter One

Suffering: The Problem of Existence

First Magnificent Vow of the Bodhisattva:

I vow to rescue the boundless living beings from suffering.

The Buddha toils through eons for the sake of living beings

Cultivating limitless, oceanic, great compassion.

To comply with living beings, he enters birth and death,

Transforming the multitudes everywhere, so they become pure1.This vow corresponds to the Noble Truth of Suffering.

What, Bhikshus, is the Noble Truth of Suffering? Birth is suffering; old age is suffering; sickness is suffering; death is suffering; sorrow, lamentation, pain, grief, and despair are suffering; to be together with what or those you hate is suffering; to be separated from what or those you love is suffering; not to obtain what you wish for is suffering; in general, identification with the Five Constituents of Existence (physical form, feeling, thoughts, volitional formations, and consciousness) is suffering2. The Truth of Suffering should be understood.

To mention the “problem” of existence already implies there is something wrong with life as we experience it. What is the problem? The Buddha’s own life provides an insight.

The Buddha, Shakyamuni, whose name means “Sage of the Shakya clan,” was born about 2500 years ago in Kapilavastu, India. His father was a ruler of one of the many kingdoms comprising India at that time. Upon his birth, seers predicted his son would either become a great world-ruling monarch or would renounce the mundane life to become a fully enlightened sage, a Buddha, who would teach countless living beings to find a genuine happiness that transcends the world.

The king, fearing his son might renounce the throne, took special precautions in his son’s upbringing to prevent him from observing the sufferings of the world. His son the prince, continuously enjoyed the myriad pleasures of life and did not come into contact with any of its pains. Through his youth the Buddha-to-be enjoyed separate palaces for each season. It is that he never even left the palace grounds. Thus the prince’s experience of life resembled a heaven on earth.

At nineteen the prince asked his father if he could take his first excursion outside the palace grounds. The king reluctantly consented but made sure that along the highway his son would encounter no one maimed, ages, or sick.

The prince, however, on his first excursion outside the palace grounds had the following experiences:Old Age

At that time the king of the Pure Abodes Heaven3 suddenly appeared at the side of the road transfigured as an old, decrepit man in order to stir repugnance in the prince’s heart. The prince saw the old man and was startled. He asked his charioteer, “What kind of person is this with white hair and bent-back? His eyes are dim; his body wobbles. He leans on a cane and walks feebly. Has his body changed unexpectedly, or is this just the way things are naturally?

The charioteer’s mind wavered. He dared not answer true. Then the god from the Pure Abodes Heaven, with his spiritual powers, caused him to speak truly. “His form’s decayed; his energy almost gone. Much distress and little happiness mark his life. Forgetful now, his sense faculties are wasted. These are the attributes of old age. Originally he was a suckling child, long-nurtured at his mother’s breast. Then as a youth he cavorted and played about handsome, unrestrained, enjoying sense desires. However, as the years went by, his body withered and decayed. Now old age has brought him to ruin.”

The prince heaved a long sigh, and then asked the charioteer, “Is he the only one who has become decrepit and old, or will we all like this become?”

The charioteer answered him again, “This lot in life alike awaits the Venerable One. As time goes on your body will naturally decay. This certainly, without doubt, will come to pass. All those young and energetic, will grow old. This, all in the world know, yet still they seek for pleasure.”

The Bodhisattva had long cultivated the karma of purity and wisdom, and widely planted the roots of every virtue. The fruits of his vows were now blossoming. Hearing these words on the suffering of old age, he shivered; his hair stood on end. Like a terrified herd of animals flees the bolt of a thunder clap, the Bodhisattva in the same way trembled with fear, as he deeply sighed and contemplated the suffering of old age.

He shook his head and steadily gazed pondering the agony of old age. “How can people find delight in the pleasures of the world when old age brings it all to ruin? It affects everyone; none escape it. For a time the body may be robust and strong, but everything’s subject to change. Now my own eyes behold the truth of old age, how can I not be disgusted and wish to leave it?”

The Bodhisattva told the charioteer, “Quickly turn the chariot around and go back. Unable to forget that old age will call for me, what happiness could I find in these gardens and groves?” Obeying the command, he drove as fast as the wind, and quickly returned to the palace.

The prince mulled over the experience of old age. The palace felt like a desolate graveyard. Everything he touched left him numb and cold. His heart could find no peace. The king heard that his son was unhappy, so he urged him to take another excursion. He ordered all of his officers to make everything more resplendent than before.

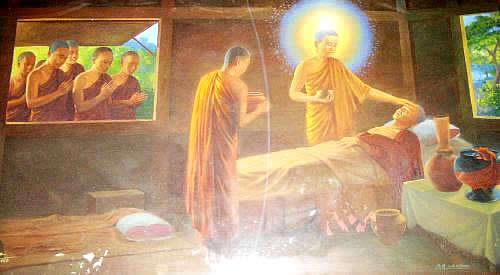

SicknessThe god again transformed himself, this time as a sick person, barely holding on to his life at the side of the road. With a gaunt body and bloated stomach, slow, asthmatic breath, stooped with withered hands and legs, he sorrowfully wept and moaned.

The prince asked the charioteer, “What kind of person is this?” The charioteer answered, “This is a sick person. The four great elements composing his body are completely out of balance. Emaciated and weak he is unable to do much of anything. Tossing back and forth, he has to rely on others.”

Hearing this, the prince’s heart swelled with pity. He then asked, “Is it only this person who gets sick, or are others subject to the same?”

He answered, “In this world everyone will also get diseased. Sickness plagues all who have a body. Yet foolish people seek joy in the fleeting pleasures of the world.”

The prince heard this with horror and dismay. His mind and body shuddered like the shimmering moon in troubled water. “Adrift on this ocean of great suffering, how can one be at ease?” He sighed for people in the world, so deluded, confused, and obstructed. “The thief of sickness can come at any time. Yet they seem happy and delighted.”

“Then he had the chariot turn around and go back, his mind distraught about the woe of sickness. He was just like someone who, about to be beaten, curls his body waiting for the clubs to fall. He quietly stayed in the palace, aspiring only for a happiness beyond the world.

The king inquired the reason for his son’s return. He was told the prince had seen a sick person. The king was aghast and totally beside himself. He severely reprimanded the people who had prepared the road. But they too were perplexed and could not explain what had happened.

Then more songstresses were sent to the Prince’s harem. Their music was more exquisite than before. The King hoped the prince, enamored by song and dance, would grow infatuated with the world and not abandon the householder’s life. Day and night came offerings of lovely women and song, yet he was not happy at all.

The king himself traveled in search of gardens, wondrous and fine. He also selected the most fair and voluptuous maidens for the Prince. They fawned on him; with all their talents served him. They were so stunning, one look at them befuddled men.

He adorned even more the royal road so all impurities were out of sight. He ordered once more the good charioteer, to carefully cleave to the gilded path.Death

At that time the god from the Pure Abodes Heaven transfigured into a corpse. Four people carrying the cadaver appeared right before the Bodhisattva. Only the Bodhisattva and the charioteer saw this. No one else was aware of it. He asked, “What is this body, with flowers and banners adorned? Those trailing behind are all grief-stricken. Their hair hanging down, they wail as they follow along.”

The god again inspired the charioteer. Thus he answered, “This is a dead person. All of his organs have deteriorated; his life has been cut off. His mind has scattered; his consciousness has left. His spirit has departed and his body has withered. It is rigid and straight like dry wood. Formerly all of his relatives and friends adored him. They bathed in mutual affection. Now none of them even wish to see him. They will shun and abandon him in an empty graveyard.” When the prince heard of death his heart ached; he felt all bound up. He asked, “Is it only this person who dies, or is everyone in the world destined to the same?”

He answered, “Each and every one must die. Whatever has a beginning, also must end. The old, the young, and those middle aged, anyone who has a body, is subject to decay.”

The prince was shocked. His body leaned forward over the railing of the chariot. His breathing halted and he sighed, “Why are people in the world so deluded? Everyone sees that their body will perish, yet they still go through life so casually. They are not insensible like dead wood or stone. Yet they never think about the impermanence of life.”

He ordered the charioteer to turn back home “This is no time for a pleasure ride. Life can end at any time. How could I indulge in an excursion?”4These experiences compelled the prince to renounce the common life to find the path beyond birth and death. His father, however, was adamant that he remain in the palace. The prince promised to stay if his father could guarantee four things:

Only under four conditions will I abandon my resolve to leave the householder’s life.

Guarantee my life will last forever; that I will be without sickness or old age, and that all my material wealth will never perish. Then I will respect your order and not leave the householder’s life.

If these four wishes cannot be fulfilled, let me leave the householder’s life. Please do not attempt to thwart me. I am in a burning house. How could you not let me out?”5The prince did leave the palace to undertake a spiritual quest to solve the problem of existence. Six years later he became a Buddha, a fully Awakened One.

The Noble Truth of Suffering suggests that a deep malaise permeates our life. Everything that we live for, everything that is dear to us will eventually be lost: our fathers and mothers, our sisters and brothers, our sons and daughters, our husbands or wives, and eventually even our own lives. Death takes everything away. This is a very serious matter both because it is inescapable and real, and moreover because paradoxically the inevitability of death gives direction and meaning to life. The Bodhisattva feels a oneness with and resulting great compassion for all beings who undergo suffering. Thus he follows the Buddha’s path to Awakening to help all beings end suffering and attain true happiness.I will be a good doctor for the sick and suffering. I will lead those who have lost their way to the right road. In will be a bright light for those in the dark night. I will enable the poor and destitute to discover hidden treasures. The Bodhisattva impartially benefits all living beings in this manner….

Why is this? Because all Buddhas, the Thus Come Ones,6 take a heart of great compassion as their very substance. Because of living beings they have great compassion. From great compassion the Bodhi-mind is born; and because of the Bodhi-mind,7 they accomplish the Equal and Proper Awakening.8

Therefore, great compassion for all the myriad living beings who are suffering in Samsara is the catalyst for making the profound resolution to become a fully Enlightened Buddha, that is, for generating the Bodhi-mind.

The Meritorious Qualities of the Bodhi-Mind

You should know that the Bodhi-mind is completely equal to all the merit and virtue of all dharmas taught by the Buddha. Why? It is because the Bodhi-mind produces all practices of the Bodhisattvas. It is because the Thus Comes Ones of the past, present, and future are born from the Bodhi-mind. Therefore, good young man, if there are those who have brought forth the resolve for Anuttara-Samyak-Sambodhi,9 they have already given birth to infinite merit and virtue and are universally able to collect themselves and remain on the path of All-wisdom…

Good young man, it is just the way a single lamp, if brought into a dark room, is able to totally eradicate a hundred thousand years of darkness. The lamp of the Bodhi-mind of the Bodhisattva, Mahasattva10 is that way too, in that upon its entering the room which is the mind of a living being, the various dark obstacles of all the karmic afflictions11 from hundreds of quadrillions of ineffable numbers of eons can all be totally destroyed.12____________________________________________________________________

1 Rulers of the World, Chapter 1, Flower Adornment Sutra.

2 Turning the Dharma Wheel Sutra, Dhamma Cakka Ppavattana Sutra.

Samyutta Nikaya LVI, 11

3 Refer to Appendix I, Chart of Samsara, The Realm of Birth and Death. The Pure Adobes are the Five Heavens of No-Return in the Form Realm.

4 Acts of the Buddha (Buddhacharita), by Bodhisattva Ashvagosha composed in the 1st century BC or AD.

5 ibid.

6 “Thus Come One” is one of the ten titles of the Buddha. See Chapter 4 for the entire list of ten.

7 The Bodhi–mind is the catalyst for the Bodhisattva path. Refer to the section on the Bodhisattva under the heading, “The Sangha of the Sages” in Chapter 5.

8 Universal Worthy’s Conduct and Vows, Chapter 40, Flower Adornment Sutra,

BTTS.

9 Anuttara-Samyak-Sambodhi literally the “Unsurpassed, Right and Total Enlightenment” meaning the ultimate Enlightenment of a Buddha.

10 Mahasattva literally means “great being”, that is, a great Bodhisattva.

11 See Chapter 2 for karma and afflictions.

12 Entering the Dharma Realm, Chapter 39, Volume 8, Flower Adornment Sutra, BTTS.Copyright © Buddhist Text Translation Society

Proper Use, Terms, & Conditions